We heard last Monday that Google have been ruled “a monopolist” in their 2020 civil antitrust case. This is big news on its own (echoing back to the Microsoft antitrust suit of 1998, which focused on bundling software with Windows) and a worrying signals for Big Tech as a whole.

It’s not the only Google suit going through the U.S. courts, however, so let’s take a look.

United States v. Google LLC

2020 Civil Antitrust: Search and Search Advertising Markets

Filled in 2020 by Department of Justice and eleven states, aiming to:

“stop Google from unlawfully maintaining monopolies through anticompetitive and exclusionary practices in the search and search advertising markets and to remedy the competitive harms.”

We’ve seen public filings emerge with details of the claims being made, and as of Monday 5th August we heard the result. Judge Amit P Mehta found that “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly”

The spotlight was on general search services and Google’s dominant market share, sitting globally at 91.4%, with its nearest competitor, Bing, at just 3.4% (despite being backed by Microsoft, the second-largest company in the world).

Given these stark numbers, Google argued that they simply got to this point by providing a better product than their competitors—something many would agree with.

However, Google was not found to have held a monopoly in search advertising. This was based on the 74% market share they hold here, in part due to the existence of other types of product listing ads, such as those sold by Amazon.

Interestingly, though, the court did find that “Google has exercised its monopoly power by charging supracompetitive prices for general search text ads. That conduct has allowed Google to earn monopoly profits”, with details emerging during the trial on how pricing practices, such as Randomised GSP and bid squashing drive up Google’s revenue (and advertisers' CPCs)

While no remedies have been suggested and there will be an inevitable appeal, the next milestone is September 4th 2024, when discussions on what the remedy will look like begin. Based on what was presented, it seems likely Google will be asked to abandon deals with partners such as Apple or Mozilla, which incentivize them to set Google as the default search engine in their products.

These lucrative revenue-sharing deals involve Google paying a percentage of the search revenue they make from partners' products where they are set as the default search engine. We heard during the trial that Google sends a massive 36% of the revenue they make from Safari queries back to Apple.

If these deals are abandoned, we’ll need to see how market share shifts once all is said and done. “Googling” is still synonymous with search, although we’re seeing some nascent competition in the form of SearchGPT or Perplexity, envisioning a world where search rankings are intertwined with LLMs (large language models).

United States v. Google LLC

2023 Civil Antitrust: Digital Advertising Technologies Market

Filled in 2023 by the Justice Department and eight states, this suit alleges that Google:

“monopolizes key digital advertising technologies, collectively referred to as the ‘ad tech stack,’ that website publishers depend on to sell ads and that advertisers rely on to buy ads and reach potential customers”.

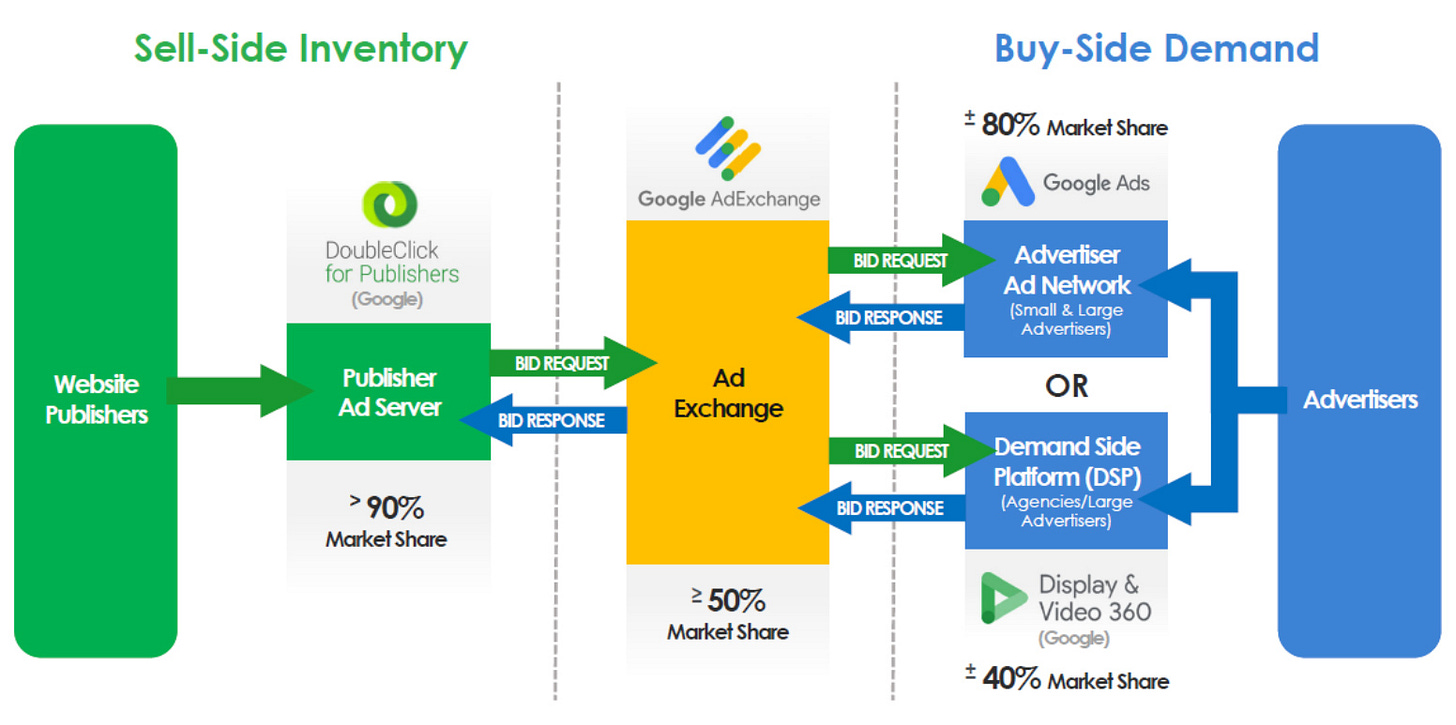

The focus is less on how Google competes as a search engine in the market and more on the critical (and perhaps outsized) role it plays in the digital marketing ecosystem. When you’re buying or selling an ad placement on the open web, it is likely that Google is taking a cut in some form.

This graphic neatly sums up this dynamic, showing Google's market share through its various products on both the sell-side and buy-side:

Claims made as part of this case also include:

Acquiring Competitors: Engaging in a pattern of acquisitions to obtain control over key digital advertising tools used by website publishers to sell advertising space;

Forcing Adoption of Google’s Tools: Locking in website publishers to its newly-acquired tools by restricting its unique, must-have advertiser demand to its ad exchange, and in turn, conditioning effective real-time access to its ad exchange on the use of its publisher ad server;

Distorting Auction Competition: Limiting real-time bidding on publisher inventory to its ad exchange, and impeding rival ad exchanges’ ability to compete on the same terms as Google’s ad exchange

Auction Manipulation: Manipulating auction mechanics across several of its products to insulate Google from competition, deprive rivals of scale, and halt the rise of rival technologies.

Unlike the 2020 suit, where there may be a clearer resolution to the complaint (through removing revenue share deals that heavily incentivize partners to set Google as the “default” search option), Google’s acquisition of technology and companies such as DoubleClick over the decades has led to its ubiquity in the AdTech world.

The start date for this trial is 9th September 2024.

Looking Towards Europe

While the above are both U.S. cases, it’s interesting to see how Google has been handling antitrust troubles in the EU related to CSEs (comparison shopping engines) and its own Google Shopping product.

In response to a 2017 EU ruling, Google introduced its own remedy in the form of the CSE Partner Programs to address these concerns. This allowed CSE partners to compete alongside Google themselves in their Product List Ad slots, placing ads on behalf of brands.

To this day, running with a CSE partner can net you up to a 20% CPC reduction, with an £0.80 bid by a CSE partner being valued the same as a £1.00 bid through the default “Google Shopping” CSE that all advertisers can use.

For advertisers, this is a clear win, and from a user perspective you’re not likely to notice much difference beyond the somewhat odd names beneath where you are clicking. It’s debatable how much traditional CSEs have truly benefited from this change and how much of an open comparison shopping market Google has really created.

The image above shows CSEs being run by Croud (a full-service digital marketing agency) and Feedoptimise (a feed management platform). They are not alone in running CSEs, with many other marketing agencies also doing so. While its clear providing the best comparison shopping engine experience to users may not be the primary focus of these businesses, under Google’s CSE partner model it makes sense they offer this service to their advertising clients.

We’ll have to see if Google takes a similar approach if it comes down to remedies in their U.S cases, and whether they again table becoming both a market operator and participant (and if this would be accepted by the courts). As of 2024, Google is still appealing still appealing the $2.6 billion fine imposed as part of the 2017 EU ruling.

What Comes Next

One key difference is that the Department of Justice was pushing for the 2023 trial to be held before a jury rather than ruled on by a judge. Ultimately, they were not successful, with the trial now being held before a judge. It would have certainly been interesting to see how the arguments would have been presented to a jury, given the complex and interconnected world of AdTech.

September is shaping up to be a busy month, with updates expected on the 2020 case and the commencement of the 2023 trial. This legal action could potentially reshape Google’s role in the market, or we could see a successful appeal or ultimately an agreement on remedies.